From Ink to Pixels: European graphic novels-turned-video-game pioneers, Part 3 – Nikopol

- 0 Comments

When it comes to video game adaptations, for many people the terms ‘comic book’ and ‘superheroes’ are largely interchangeable. There have been some notable exceptions over the years, however, beginning in the early 2000s when some of Europe’s most celebrated non-superhero comic books were adapted with input from their original creators – some more successfully than others. Continuing my earlier examinations of Salammbô: Battle for Carthage and Druuna: Morbus Gravis, this multi-part article series concludes with the third of three pioneering games that stand out in my personal experience as the most interesting interpretations of their source material. They may not have left much of a lasting impression in their own right, but they helped blaze a trail for other comic book franchises to succeed where their predecessors did not.

Nikopol: Secrets of the Immortals

Enki Bilal’s La Foire aux immortels (translated Carnival of Immortals), the first volume of his Immortal trilogy, was published by Darguad as a hardcover bande dessinée in 1980. An English translation in Heavy Metal magazine followed over the next year, and is widely regarded as a work of art in the graphic novel medium.

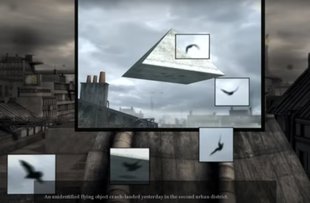

Carnival of Immortals chronicles the adventure of Herakles Nikopol, Baudelaire fan and deserter, who refuses to fight with the French military against the Sino-Soviet coalition in 1992. As a result of his protest, Nikopol is sent into space to serve a prison sentence in cryogenic sleep. While serving his time, the ancient Egyptian gods return to Earth from outer space. Their spaceship (the Great Pyramid) has stalled over Paris, and the pantheon notes that Horus is nowhere to be found. Having escaped the ship, Horus searches for a host to do his bidding. Nikopol, it turns out, is the most suitable specimen. Freeing the prisoner from his sleep chamber via a rude crash-landing into 2023 Paris, Horus possesses the still-frosty Nikopol and begins his escapade.

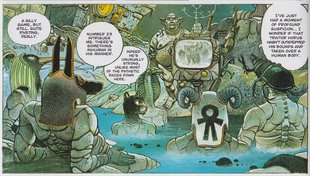

The book was followed by two sequels, The Invisible Woman and Cold Equator, further expanding Bilal's surreal science fiction story. His world is grimy and polluted, each frame brimming with extraordinary detail highlighting decades of decay and corruption. Bilal’s signature mixed technique style layers coloured pencils and watercolour paint with delicate, perfectly calculated hatching. A haunting cast of characters, like Jill, a woman with pale white skin and blue hair, and the Egyptian deities, with their animal faces and sculpted statuesque bodies, populate Bilal’s satiric and unsettling dystopia. The Carnival of Immortals trilogy is filled with humour and horror, imagining a European society plagued by conflict.

A storied history

In 2004, Bilal adapted his story to the big screen in the film Immortal. Bilal rewrote the story of the original books for Immortal, altering some of the characters’ origins and moving the setting to New York from Paris. The film heavily utilized green screens to create backdrops, melding human actors with computer-generated characters and sets. Quantic Dream, developers of Omikron and Fahrenheit/Indigo Prophecy, assisted with character design and animation.

Quantic Dream would not be Nikopol’s only attachment to the video game world, however. In 2008, Bilal would once again readapt his story, working with White Bird Productions and Benoît Sokal (himself an acclaimed comic book artist-turned-game designer with his acclaimed Syberia series) to develop his story into a video game. The team went to work, creating an art style White Bird’s co-founder Michel Bams described in a 2008 interview with Diehard Game Fan as “somewhere between the original graphic novel and the movie.” Bilal oversaw development, even contributing new character and design art for the team to work with.

Nikopol: Secrets of the Immortals has players assume control of the son of Herakles, Alcide Nikopol, in 2023 Paris. The city is ruled by a fascist government, with a literal wall dividing the city’s rich and poor citizens. One day, a mysterious pyramid appears overtop of Paris. Soon after, Nikopol receives word that his father, whom he has never met, may in fact be alive and is being held somewhere in the city. Alcide sets out to locate his father, but quickly finds himself entangled in a dangerous conflict between rebels and members of the ruling class.

Certain aspects of the story were changed for the game, some due to social context (like the Cold War setting), and others for adapting it to video game format. Ultimately, White Birds wanted the end product to be both approachable for fans and newcomers of the series.

Bilal’s artwork was adapted into pre-rendered backdrops for Nikopol, with players moving through spaces in a first-person, node-based fashion with 360-degree camera panning. The game features an aesthetic that's cleaner and more realistic than Bilal’s drawings, but still evoking the same atmosphere of cyberpunk decay, with new buildings towering over the rundown streets and homes of the old city. Environments are rarely static, with details like hovercars speeding by Nikopol’s apartment window and giant alien creatures pacing back and forth lending the presentation a real-time atmosphere.

The game is fully voiced, with Nikopol providing fluid, noir-like commentary throughout. Cutscenes play out as segmented comic book frames that pan and move across the screen, forming full-page motion comics that make for a stylish presentation evocative of the source material.

Nikopol is a point-and-click adventure at heart, with inventive (and topical) challenges, like painting a portrait by laying foundations onto a canvas in a specific order. Other puzzles are more mathematical in nature, like one requiring players to painstakingly decode a message with an alphabet of scrambled characters. However, the game also incorporates some action elements, forcing players to think and act quickly in shooting and chase segments.

The judgement of Paris

Bilal was satisfied with the game, with Michel Bams recalling him praising the team’s efforts. However, when reviews began coming in, the response proved divisive. Some criticized the puzzles for being obtuse, while others enjoyed the setting and found the game immersive. Almost all agreed the art design (supervised by Bilal) was spectacular, and the stylish comic book-style cutscenes were a treat, though the story itself was hard to follow.

Personally I enjoyed the game. The difficulty level could be inconsistent, with the second chapter in particular holding me hostage for longer than I like to admit, but after each hurdle the game continued to surprise and entertain me. It’s relatively short, and while the story isn’t as memorable as the original graphic novel or movie, it proves a highly immersive, suspenseful, and challenging (albeit maybe a bit too challenging at times) adventure game. The action and timed sequences are good fun, and the puzzles are suitably creative. There are minor frustrations to be found, but it’s easy to recommend to adventure gamers who like cyberpunk, as well as fans of Bilal’s work who are interested in exploring one of his fascinating futuristic worlds first-hand.

Nikopol: Secrets of the Immortals was the first and only game adapted from Bilal’s graphic novel trilogy, and I was sorry to see it not continued because the remainder of the comic series held great potential for more adventure adaptations. (I would have loved to see what White Bird could have done with Cold Equator’s Chess Boxing.)

Having been re-released digitally, the game is available for download on Steam, GOG and the Epic Game Store.

Out of ink

It’s hard to say whether any of these three adaptations had a notable impact on their respective franchises. Salammbô: Battle for Carthage was perhaps the best-received of the bunch, and along with Nikopol: Secrets of the Immortals is still available for purchase. Druuna: Morbus Gravis, predictably, has faded into obscurity and will likely never see a digital release. That said, several more Druuna comics have been published since the game’s release, meaning there was still a lot of goodwill left towards the character and her creator outside of gaming circles.

But perhaps the greatest benefit of such adaptations is in paving the way for more video games based on graphic novel properties since then, with still more to come. In Europe, Artematica got another shot at developing a comic book license with 2009’s Diabolik: The Original Sin, based on the Giussani sisters’ famed Italian comic Diabolik, faring better than their work on Druuna years earlier. Canales and Guarnido’s Blacksad received the video game treatment in the generally well-received Blacksad: Under the Skin in 2019, by Microids, YS Interactive and Pendulo Studios. Microids also obtained the Tintin license from the Herge Foundation, and while their first release, Tintin Reporter: Cigars of the Pharaoh, didn’t quite live up to expectations, there was still considerable interest in seeing the character back on screen.

The trend towards graphic novel adaptations has reached North American shores as well. Robert Kirkman’s The Walking Dead earned significant acclaim for its narrative-driven video game adaptations from Telltale, as did The Wolf Among Us, based on Bill Willingham’s Fables comics. The company would go on to produce a pair of Batman games as well (superhero comics are still very much alive and well in video game form), but even they were designed in Telltale’s signature storytelling format – a far cry from the Dark Knight’s fisticuffing forays in earlier games, showing just how impactful a character- and story-focused adaptation could be.

This long after their respective releases, the three games examined in this series will likely only appeal to the small group of people who happen to be fans of both European graphic novels and the adventure game genre. In this regard, despite some (or many) frustrations in gameplay, all three are worth investigating, if mainly to see the artists’ visions at work in a new medium. For the industry at large, however, their enduring legacy may just be that they helped broaden the definition of ‘comic book video games’ to something much more inclusive than what came before.

0 Comments

Want to join the discussion? Leave a comment as guest, sign in or register.

Leave a comment